Page 220 - 亚洲二十世纪及当代艺术

P. 220

“Painting must have feeling,

it must resonate with one’s

own heart. Only with a lively

inner self can creativity

remain alive, and only then

can the painting always

remain alive.”

{{ Liu Wei

After experiencing the rise of the

avant-garde in the 85 New Wave

and the collective contemplation

of the 1989 China/Avant Garde

exhibition, Chinese contemporary

artists in the 1990s gradually

achieved a leap towards an

international perspective,

undergoing a transformation

8

d

̺

Ò

3

1.

؍

ኁ

ذ

d

ϋ

888

1

৷ඉࢨኁ؍ٙӽ྅dذ̺d81.2Ò65.3 cmd1889 ϋ

dت

Ъ

.

5

6

d

m

4 c

৷ඉࢨኁ؍dذ̺d81.3Ò65.4 cmd1888 ϋЪdت ৷ ඉ ࢨ ኁ ؍ ٙ ӽ ྅ d ذ ̺ d 8 1. 2 Ò 6 5 . 3 c m d 18 8 9 ϋ

৷

ࢨ

ඉ

Ъdஃᚆෳतݾдਔਔ - Ϸਔ௹يᔛ

ɻߕஔᔛ

ɻ ߕ ஔ ᔛ Ъ dஃ ᚆ ෳ त ݾ д ਔ ਔ - Ϸ ਔ௹ ي ᔛ of thought, change in form,

and multiple influences from

ӽ྅˴ᕚdνϘಂՈ݁طܠ፫ٙࠧնࢬӻΐdɛ݊˼ɓٜชጳሳٙ˴ᕚdϾ reality. They bid farewell to their

ί 2009 ϋd˼̤ᚠᒌࢰή͂ॎɓٜ˸Ըί̺ձॷ͉ɪٙ೯౨dΫ๑ኪ͛ࣛ˾کኸ previous explorations of history,

ڗٙ˝Սd࢝ତՉɦɓᖵஔᜳΈf

philosophy, and value systems,

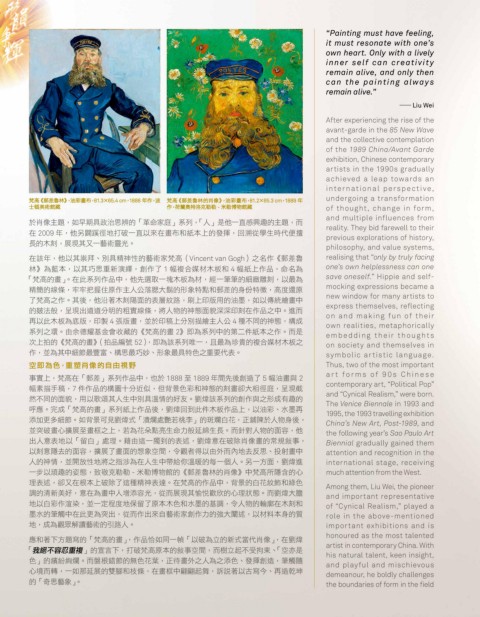

ί༈ϋd˼˸Չक़ܰeйՈၚग़ٙᖵஔ৷Vincent van GoghʘΤЪඉࢨኁ realising that “only by truly facing

؍މᔝ͉d˸Չ̷ܠࠠอစᖫd௴Ъə 1 షልΥదҿ˝ؐձ 4 షॷɪЪۜdնΤމ one’s own helplessness can one

৷ٙfίϤӻΐЪۜʕd˼፯՟ɓ෯˝ؐމҿdɓഅഅٙᇘᎉՍd˸௰މ save oneself.” Hippie and self-

ၚᔊٙᇞૢdӪӪҪИࡡЪ˴ɛʮໝ໓ɽᗻٙҖतᓃձඉࢨٙԒ΅तᅄd৷ܓᒔࡡ mocking expressions became a

ə৷ʘЪfՉܝd˼ضഹ˝Սජࠦٙڌᄴ७༩dՏɪΙوٙ͜ذኈdν˸ෂ୕ᖭʕ new window for many artists to

express themselves, reflecting

ٙೲجছdяତ̈༸༸ʱٙྼᇞૢdਗ਼ɛيٙग़࿒ࠦႶଉଉΙՍίЪۜʘʕfආϾ on and making fun of their

Ύ˸Ϥ˝ؐމֵوdΙႡ 4 ੵوdԨΙᇃɪʱйᖭ˴ɛʮ 4 ၇ʔΝٙग़࿒dϓ own realities, metaphorically

ӻΐʘᐑf͟Яᅃᘴਿږึϗᔛٙ৷ٙ 2уމӻΐʕٙୋɚॷ͉ʘЪfϾ݊ embedding their thoughts

ϣɪשٙ৷ٙשۜᇜ 52dуމ༈ӻΐਬɓd˲௰މޜ൮ٙልΥదҿ˝ؐʘ on society and themselves in

ЪdԨމՉʕື௰ᔮబeܠ௰̷ѶeҖ௰ՈतЍʘࠠࠅ˾ڌf symbolic artistic language.

٤уމЍdࠠ෧ӽ྅ٙІ͟ൖ Thus, two of the most important

ar t f o r m s o f 9 0 s C hin e s e

ԫྼɪd৷ίඉࢨӻΐЪۜʕdɰ 1888 Ї 1889 ϋගܝ௴ிə 5 షذၾ 2

ష९˓ᇃd7 ЪۜٙྡɤʱڐЧdШߠ౻Ѝձग़࿒ٙՍۍɽࢰࢬdяତ࿚ contemporary art, “Political Pop”

and “Cynical Realism,” were born.

್ʔΝٙࠦႶd͜˸ဂՉɛ͛ʕйՈઋٙλʾfᄎ⑸༈ӻΐٙ௴ЪၾʘҖϓϞሳٙ The Venice Biennale in 1993 and

խᏐfҁϓ৷ٙӻΐॷɪЪۜܝdᄎ⑸ΫՑϤ˝ؐЪۜɪd˸ذe˥ኈΎ 1995, the 1993 travelling exhibition

̋һεືfνߠ౻̙Ԉᄎ⑸όᆖᙻஈᜮࣹ߰ҽٙᙴͣڀd͍ɛيԒܝd China’s New Art, Post-1989, and

Ԩ߉ॎːᓒ࢝Ї࣪ʘɪd߰މڀϢᓃڥ͛նɢছַၧ͛ڗfϾ০࿁ɛي࢙ٙࠦd˼ the following year’s Sao Paulo Art

̈ɛจڌή˸वͣஈଣfᔟ͟வɓዹՑٙڌࠑdᄎ⑸จίॎৰӽ྅ٙ੬ાԫd Biennial gradually gained them

˸Սจᒯ̘࢙ٙࠦdᓒ࢝əࠦٙซ٤ගd˿ᝈ٫˸̮͟Ͼʫή̘ˀܠeҳ࢛ʕ attention and recognition in the

ɛٙग़ઋdԨක׳ήਗ਼ʘܸऒމίɛ͛ʕ੭ഗЫาٙӊɓࡈɛf̤ɓ˙ࠦdᄎ⑸ආ international stage, receiving

ɓӉ˸ཬሳٙ۶࿒dߧหдਔਔ - Ϸਔ௹يٙඉࢨኁ؍ٙӽ྅ʕ৷הᒯўٙː much attention from the West.

ଣڌࠑdۍɦί͉࣬ɪॎৰəவ၇ၚग़ڌ༺fί৷ٙЪۜʕdߠ౻ٙͣڀ७ུձၠЍ Among them, Liu Wei, the pioneer

ሜٙอߕλdจίމʕɛᄣ࢙ΈdϾ࢝ତՉౕࣀᛇؚٙːଣً࿒fϾᄎ⑸ɽᑔ and important representative

ή˸ͣЪݑdԨɓ֛ܓήڭवəࡡ͉˝Ѝձ˥ኈٙਿሜd˿ɛيٙቃ࿊ί˝Սձ of “Cynical Realism,” played a

ኈ˥ٙഅᙃʕίϤһމ߉̈dϾЪ̈ԸІᖵஔ௴Ъɢٙ੶ɽᙕࠑd˸ҿ͉ࣘԒٙሯ role in the above-mentioned

ήdϓމᝈ༆ᛘᖵஔٙˏ༩ɛf important exhibitions and is

honoured as the most talented

Ꮠձഹɨ˙ᕚᄳٙ৷ٙdЪۜܦνΝɓహ˸ॎމͭٙอό˾ӽ྅dίᄎ⑸ artist in contemporary China. With

Ңഒʔ࢙Ҝࠠልٙ܁Ԋɨd͂ॎ৷ࡡ͉ٙાԫ٤ගdϾዓͭৎʔաҼe٤͵݊ his natural talent, keen insight,

ЍٙᘰॸഘᙻfϾᆵ࣬፹ືٙೌЍڀd͍ܙ̮ʘɛމʘЍe೯౨௴ிdഅᙃᎇ and playful and mischievous

ːྤϾᔷdɓνԟַ࢝ٙᕐ໔ձ،ૢdί࣪ʕᇨᇨৎႀdൡႭഹ˸̚ᄳʦeΎி৻տ demeanour, he boldly challenges

ٙփܠᖵf the boundaries of form in the field

18 1