Page 134 - 一色,一切色—釉瓷幻化“承色”之美

P. 134

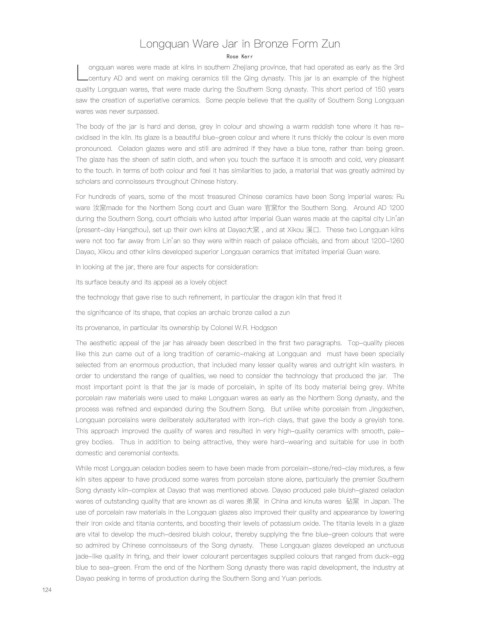

Longquan Ware Jar in Bronze Form Zun

Rose Kerr

ongquan wares were made at kilns in southern Zhejiang province, that had operated as early as the 3rd

Lcentury AD and went on making ceramics till the Qing dynasty. This jar is an example of the highest

quality Longquan wares, that were made during the Southern Song dynasty. This short period of 150 years

saw the creation of superlative ceramics. Some people believe that the quality of Southern Song Longquan

wares was never surpassed.

The body of the jar is hard and dense, grey in colour and showing a warm reddish tone where it has re-

oxidised in the kiln. Its glaze is a beautiful blue-green colour and where it runs thickly the colour is even more

pronounced. Celadon glazes were and still are admired if they have a blue tone, rather than being green.

The glaze has the sheen of satin cloth, and when you touch the surface it is smooth and cold, very pleasant

to the touch. In terms of both colour and feel it has similarities to jade, a material that was greatly admired by

scholars and connoisseurs throughout Chinese history.

For hundreds of years, some of the most treasured Chinese ceramics have been Song imperial wares: Ru

ware 汝窯made for the Northern Song court and Guan ware 官窯for the Southern Song. Around AD 1200

during the Southern Song, court officials who lusted after imperial Guan wares made at the capital city Lin’an

(present-day Hangzhou), set up their own kilns at Dayao大窯 , and at Xikou 溪口. These two Longquan kilns

were not too far away from Lin’an so they were within reach of palace officials, and from about 1200-1260

Dayao, Xikou and other kilns developed superior Longquan ceramics that imitated imperial Guan ware.

In looking at the jar, there are four aspects for consideration:

its surface beauty and its appeal as a lovely object

the technology that gave rise to such refinement, in particular the dragon kiln that fired it

the significance of its shape, that copies an archaic bronze called a zun

its provenance, in particular its ownership by Colonel W.R. Hodgson

The aesthetic appeal of the jar has already been described in the first two paragraphs. Top-quality pieces

like this zun came out of a long tradition of ceramic-making at Longquan and must have been specially

selected from an enormous production, that included many lesser quality wares and outright kiln wasters. In

order to understand the range of qualities, we need to consider the technology that produced the jar. The

most important point is that the jar is made of porcelain, in spite of its body material being grey. White

porcelain raw materials were used to make Longquan wares as early as the Northern Song dynasty, and the

process was refined and expanded during the Southern Song. But unlike white porcelain from Jingdezhen,

Longquan porcelains were deliberately adulterated with iron-rich clays, that gave the body a greyish tone.

This approach improved the quality of wares and resulted in very high-quality ceramics with smooth, pale-

grey bodies. Thus in addition to being attractive, they were hard-wearing and suitable for use in both

domestic and ceremonial contexts.

While most Longquan celadon bodies seem to have been made from porcelain-stone/red-clay mixtures, a few

kiln sites appear to have produced some wares from porcelain stone alone, particularly the premier Southern

Song dynasty kiln-complex at Dayao that was mentioned above. Dayao produced pale bluish-glazed celadon

wares of outstanding quality that are known as di wares 弟窯 in China and kinuta wares 砧窯 in Japan. The

use of porcelain raw materials in the Longquan glazes also improved their quality and appearance by lowering

their iron oxide and titania contents, and boosting their levels of potassium oxide. The titania levels in a glaze

are vital to develop the much-desired bluish colour, thereby supplying the fine blue-green colours that were

so admired by Chinese connoisseurs of the Song dynasty. These Longquan glazes developed an unctuous

jade-like quality in firing, and their lower colourant percentages supplied colours that ranged from duck-egg

blue to sea-green. From the end of the Northern Song dynasty there was rapid development, the industry at

Dayao peaking in terms of production during the Southern Song and Yuan periods.

124